In a world first, a team of international scientists, led by University of Sydney archaeologist, Dr Amy Way and Australian Museum, has revealed that early humans across southern Africa made a particular type of stone tool – a blade used for many purposes including hunting technology (such as barbs in hand thrown spears and possibly bow and arrows), for cutting wood, plants, bone, skin, feathers and flesh – in the same shape. The researchers reported this means populations must have been in contact with each other.

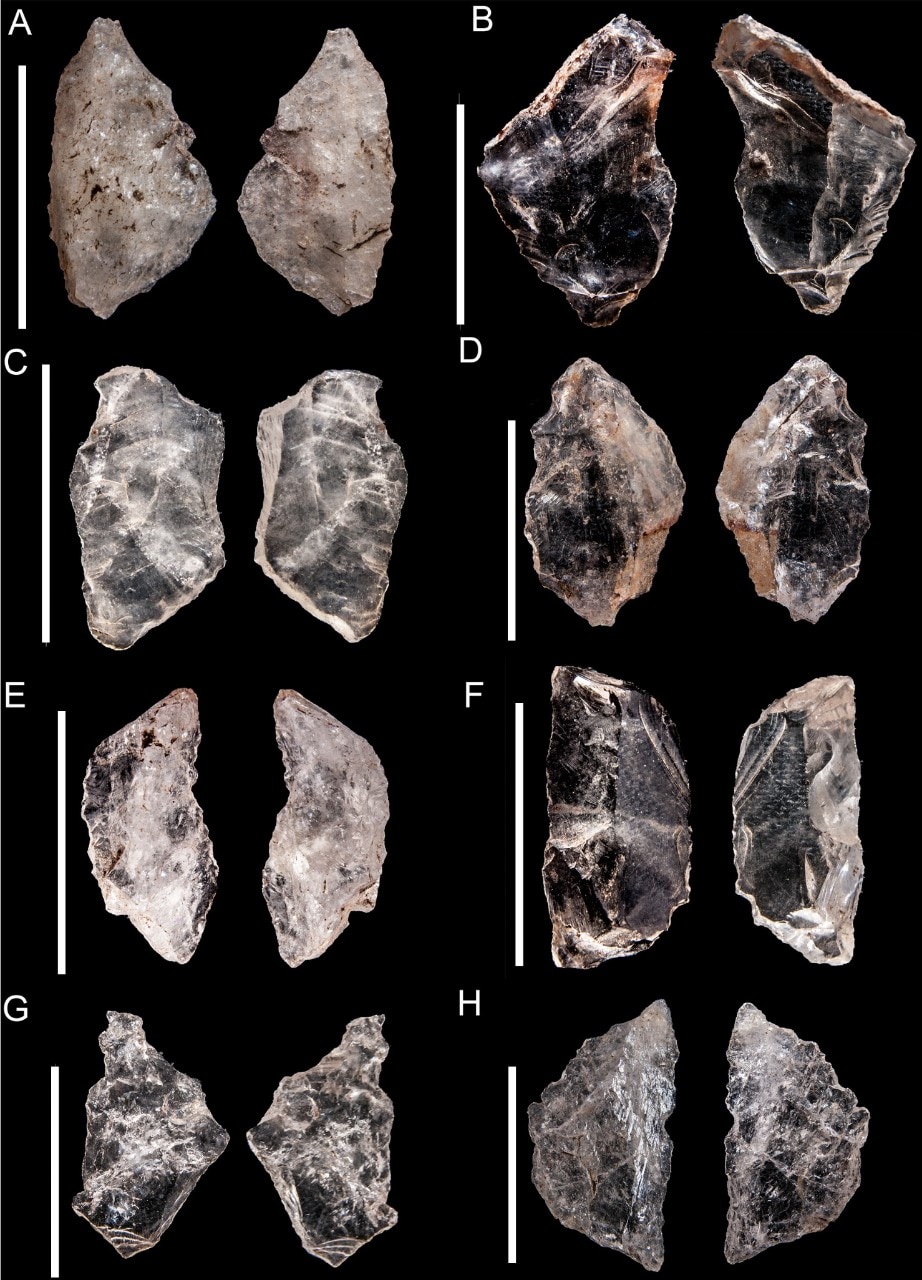

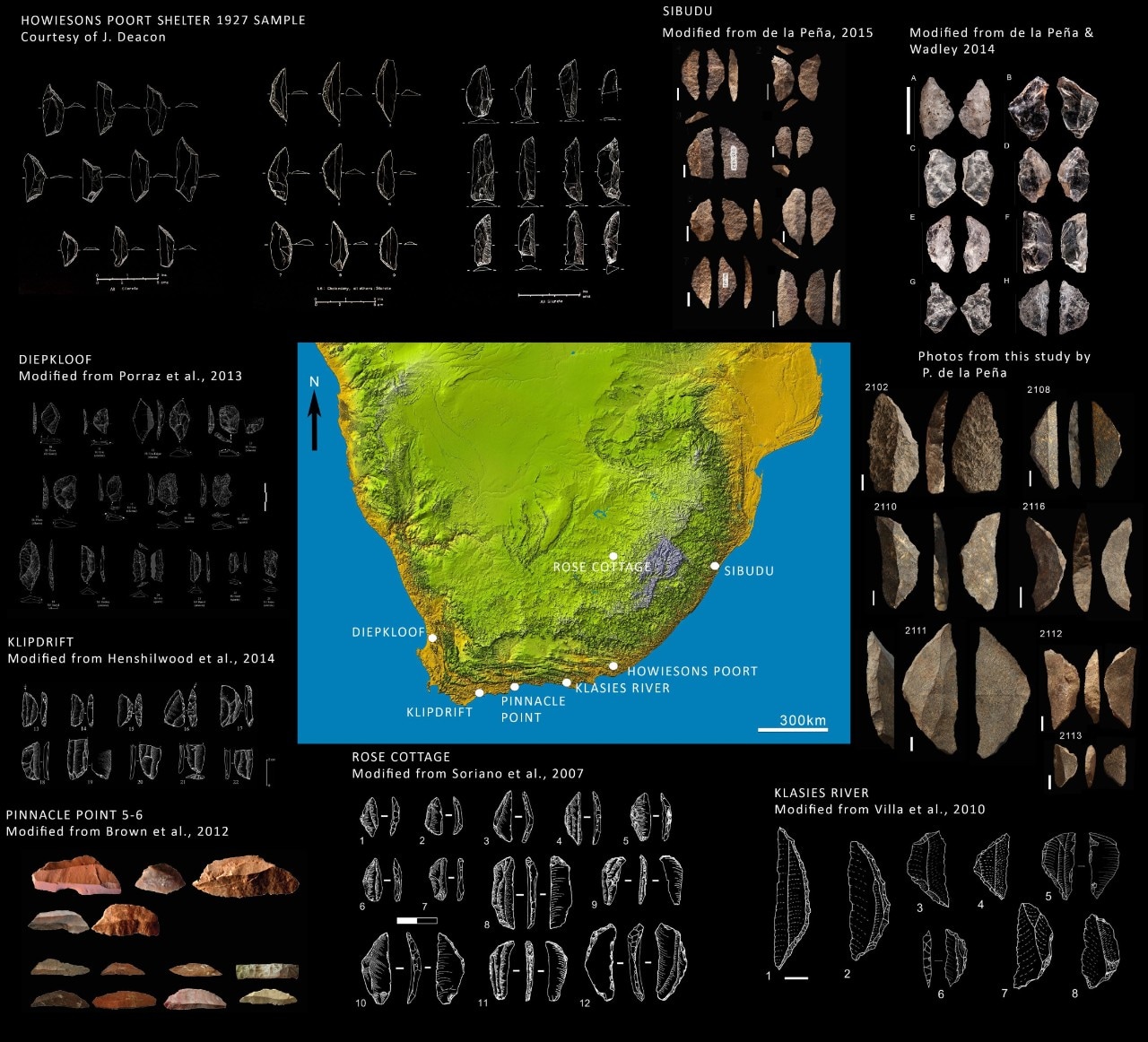

Known as the “stone Swiss Army knife” of prehistory, the Howiesons Poort blades were made to a similar template across great distances and multiple biomes. The study published in Scientific Reports, found the artefacts produced in enormous numbers across southern Africa roughly 65 thousand years ago were made to a similar shape.

Lead author Dr Way, from the Department of Archaeology at the University of Sydney and the Australian Museum, explained that these tools were made in many different shapes across the world yet the people across southern Africa all produced tools that look the same, indicating they must have been sharing information with each other – they were socially connected.

“People have walked out of Africa for hundreds of thousands of years, and we have evidence for early Homo sapiens in Greece and the Levant from around 200 thousand years ago. But these earlier exits were overprinted by the big exit around 60 thousand years ago, which involved the ancestors of all modern people who live outside of Africa today,” Dr Way said.

“Why was this exodus so successful where the earlier excursions were not? The main theory is that social networks were stronger then. This analysis shows for the first time that these social connections were in place in southern Africa just before the big exodus,” Dr Way added.

Dr Paloma de la Peña, who studies the cultural behaviour of the early Homo sapiens, at Cambridge University, said the tools have been associated with many different domestic activities such as cutting and scraping.

“While the making of the stone tool was not particularly difficult, the hafting of the stone to the handle through the use of glue and adhesives was, which highlights that they were sharing and communicating complex information with each other,” Dr de la Peña explained.

“What was also striking was that the abundance of tools made in the same shape coincided with great changes in the climatic conditions. We believe that this is a social response to the changing environment across southern Africa,” Dr de la Peña added.

Social networking

Chief Scientist at the Australian Museum, Professor Kristofer Helgen said that like us, early humans relied on cooperation and social networking, and this research provides some of the earliest dated observation of this behaviour.

“Examining why early human populations were successful is critical to understanding our evolutionary path. This research provides new insights into our understanding of those social networks and how they contributed to the expansion of modern humans across Eurasia,” Professor Helgen said.

Australian stone tools

Dr Way said another fascinating fact about this particular tool is that it was made independently by many different groups of people across the world at different times, including here in Australia.

“I compared some of the Australian shapes from five thousand years ago with the African shapes 65 thousand years ago (as they can’t possibly be related), to show the similarity seen in the southern African tools is culturally meaningful,” Dr Way said.

In southern Africa, previous research by Dr de la Peña has shown that the blades or backed artefacts were used as barbs in hunting technology. In Australia, Australian Museum Senior Fellow, archaeologist, Dr Val Attenbrow has shown that in addition to forming armatures in spears, these artefacts were also used for a variety of functions and purposes, such as working bone and hide and drilling and shaping wooden objects.

Declaration: The research was funded by the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeosciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, Australian Museum Foundation and Tom Austin Brown Research, University of Sydney.

Comments are closed.