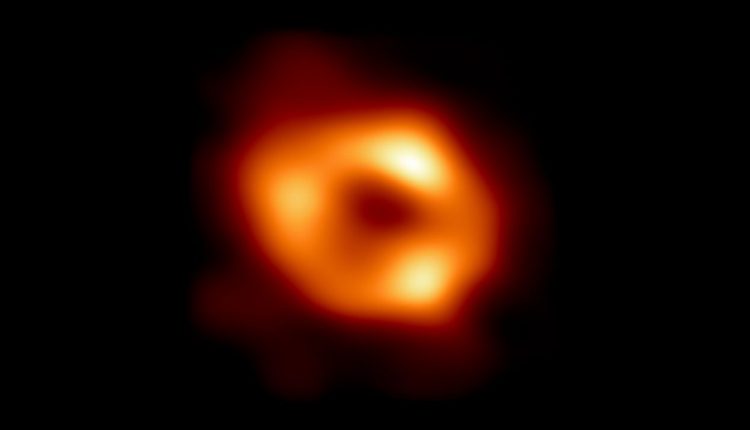

An international team of more than 300 scientists from 80 institutions has created the first-ever image of the supermassive black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy.

Called Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), the image was produced by the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration, using observations from a worldwide network of radio telescopes.

The image is a long-anticipated look at the massive object that sits at the very center of our galaxy. Scientists had previously seen stars orbiting around something invisible, compact and very massive at the center of the Milky Way. This strongly suggested that this object is a black hole, and the newly released image provides the first direct visual evidence of it.

“Being able to see the shadow of the black hole, the gas flowing around it and the blackness at its heart, is extraordinary,” said Shami Chatterjee, principal research scientist at the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S) and a member of the EHT collaboration. “We can do a lot of physics with this data – for the first time we have an actual measurement and we can compare it with predictions from general relativity, and we can weigh the monster at the heart of our galaxy and say this is exactly how much mass is in that black hole.”

Although the black hole itself cannot be seen because it is completely dark, glowing gas around it reveals a telltale signature: a dark central region (called a shadow) surrounded by a bright ring-like structure. The new view captures light bent by the powerful gravity of the black hole, which is 4 million times more massive than our sun.

Because the black hole is about 27,000 light-years away from Earth, it appears to us to have about the same size in the sky as a doughnut on the moon. To image it, the team created the powerful EHT, which linked together eight existing radio observatories across the planet to form a single “Earth-sized” virtual telescope. The EHT observed Sgr A* on multiple nights, collecting data for many hours in a row, similar to using a long exposure time on a camera.

The breakthrough follows the EHT collaboration’s 2019 release of the first image of a black hole, called M87*, at the center of the more distant Messier 87 galaxy.

Despite Sgr A* being in our backyard, because it is smaller than M87* it proved more challenging to image, said James Cordes, the George Feldstein Professor of Astronomy (A&S), a member of the EHT collaboration. “Because this black hole is smaller, the time required for the gas to orbit around it is weeks instead of months as with M87*, which means the source is more variable. It’s like trying to take a picture of something while it is flickering.”

In addition to developing complex tools to overcome the challenges of imaging Sgr A*, the team worked rigorously for five years, using supercomputers to combine and analyze their data, all while compiling an unprecedented library of simulated black holes to compare with the observations.

Chatterjee and Cordes are working with the data collected by the EHT Collaboration to search for pulsars in orbit around Sgr A*.

“Being able to find some pulsars that are orbiting the black hole will give us a completely different, complementary set of information from that which the image provides,” Cordes said. “If we can find a pulsar that acts like a precise clock orbiting the black hole in the center of our Galaxy, that will give us extraordinary new tests of the predictions from Einstein’s theory of general relativity.”

Their pulsar working group relies heavily on machine learning and AI, said Chatterjee, because of the noisiness of the data.

“With so many telescopes, there’s a lot of interference – from cell phones, from satellites passing overhead, from the telescope slewing back and forth – and all of that has to be filtered out while we look for an astrophysical signal of interest,” he said. “It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack so it’s a place where machine learning can and is playing a significant role. The machine learning identifies interesting signals and we humans can inspect them. It reduces the problem of the massive onslaught of interference into manageable proportions.”

Comments are closed.